The Geometry Of Sound - A Dialogue Between Architecture and Music

The Team Blog Series is a collection of blogs written by members of our team. Each blog's author will tell you about a topic, news, or issue that piques their interest.

Today’s blog was brought to you by Luka Shavadze, our junior architect and model maker. In this blog he will be sharing his thought about the invisible string that connect music to architecture.

“When you are an architect, you feel at home wherever you go. In New York, I’m a New Yorker. In Berlin, I’m a Berliner. In Hanoi, I’m Vietnamese. An architect cannot be a tourist. You need to understand people and listen to the place, because the place has a story to tell. If you love the place, you will feel at home.”

— Renzo Piano

— Renzo Piano

Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano during the construction of the Pompidou Centre. 1975.

Where does music live? Wherever it is being heard. The Malagueña born on the streets of Málaga in Spain comes to life for me here, in this exact moment, when I listen to it and feel it. Piano implies that an architect must internalize the place they’re working on. They must listen, understand, become part of it. This is exactly the same process that happens in music. A performer or composer absorbs and conveys the spirituality of a specific culture (often their own), era, or geographical location.

Although architecture and music may seem like two different worlds at first glance, in reality, they can be perceived as two dialects of the same language. Both are a play between noise and silence, time and space, dissonance and harmony. They serve as bridges between the physical and abstract dimensions, taking us on journeys through forms, vibrations, and emotions.

Music is the art of time; architecture is the art of space. But where is the boundary? When does one resonate with the other? Bach’s fugues, where voices intertwine to create dynamic structure, resemble a Gothic cathedral whose vertical lines, columns, and windows are arranged with the same logic—complex, yet perfectly ordered. Just like a fugue, a cathedral produces interplay between sonic elements—streams of light pouring through windows, echoes, textures, and most importantly, the presence of a human being, moving through space and changing its dynamics.

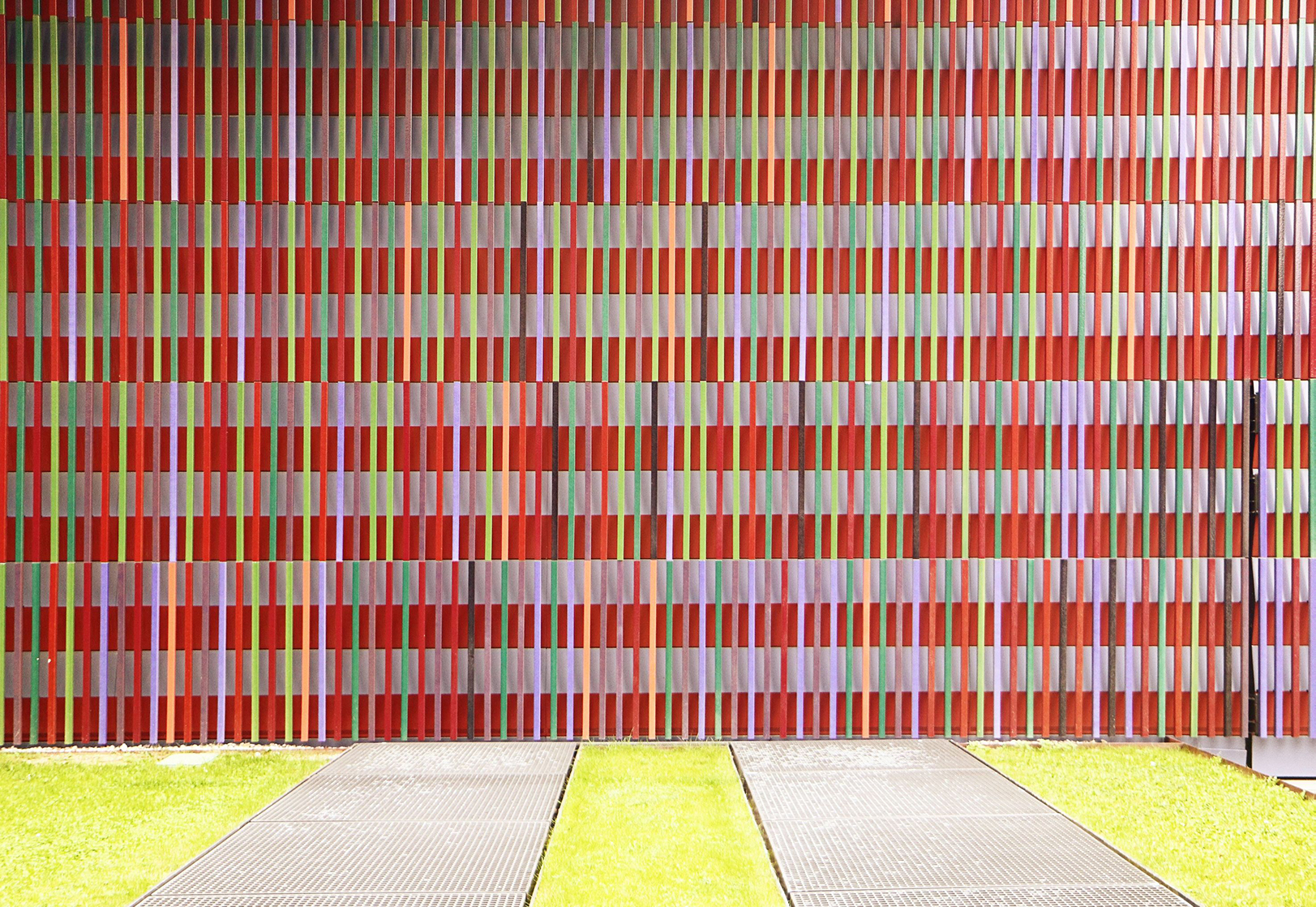

Sauerbruch Hutton, Brandhorst Museum, munich, 2008-11

There is music (in my view, all good music has this power) that creates space—and architecture that transforms into sound. Sometimes a single strong tonality or material is enough to awaken a strange emotion in the body. For instance, brutalist concrete buildings resemble the harmonious resonance of a monochromatic bass tone, while Frank Gehry’s metallic façades evoke the improvisation of free jazz. Music and architecture mirror each other not just in form but also in energy—a composer’s and an architect’s ideas may evolve in parallel, even across different times and contexts, aiming to stir the same emotion in the human soul.

Frank Gehry, Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao. 1997

Music comes alive in the space where we listen to it—and architecture pulses with the sounds within it. A musical piece cannot exist without space—acoustics define the depth of sound, resonance, even the quality of silence. In architecture, this is shaped by material choices, proportions, and spatial tectonics, which in turn shape human perception.

We can go even deeper and ask: what materials create music, and to what can they be compared? The warm sound of wood, the sharp echo of metal, the silent resonance of concrete. Some spaces seem to call for specific music—medieval monasteries are ideal for Gregorian chants, while modern glass-and-steel constructions are suited for experimental electronic sounds. But the opposite can be fascinating too—electronic music inside a monastery creates a new, unprecedented experience. In such cases, architecture stops functioning independently and becomes part of the music—an instrument through which sounds move freely and transform.

If music and architecture are so alike, why don’t we perceive space as melody? Maybe we are creating music, architecture—or at least contributing to it—without even noticing. How can we learn to listen to the city? It has its rhythm—the hum of traffic, the sound of footsteps, the loud thoughts of people sitting in the park, appearing like invisible notes in the composition. When a new building is added to the city’s sonic canvas, it’s like a new note that blends into the symphony or creates dissonance. If notes are buildings, then lines could be streets or the foundation on which a musical structure stands. The movement of a composition along musical lines can be seen as a city’s topographic map—some melodies are linear like minimalist architecture, while others are complex like the composition of a Gothic cathedral.

For me, Pink Floyd’s Echoes is exactly that piece of music—one that is not only musically, but architecturally fascinating. It is at once a musical space and an acoustic landscape that opens before us not just as a melody but as an architectural structure we can enter and get lost in for 24 minutes. It is a musically constructed architectural space.

Pink Floyd - echos – Live at Pompeii for ducumentary film, 1971

I also feel a particularly strong emotion from the video recording “Lágrimas Negras – Cuba Feliz.” The composition Lágrimas Negras carries a strong sense of mood shifts. When one tonality replaces another in music, the listener feels it, and it is precisely elements like tonality, rhythm, and similar factors that determine the emotions evoked in the listener.

Photo from the video recording "Lágrimas Negras - Cuba Feliz."

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GGubts0G-xk

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GGubts0G-xk

Just like in music, in architecture, changes in feeling and emotion become the main driving force. Drawing a parallel, I believe that beyond creating functionally sound buildings, an architect’s goal should also be to design spaces that evoke different emotions—spaces that stir curiosity in the people inside and ignite a thirst to discover what lies in the next room.